Posted originally on January 19, 2015 by Neil.

This series of posts is the most comprehensive I have done on family history. I am doing them backwards here so that in due course they will appear sequentially.

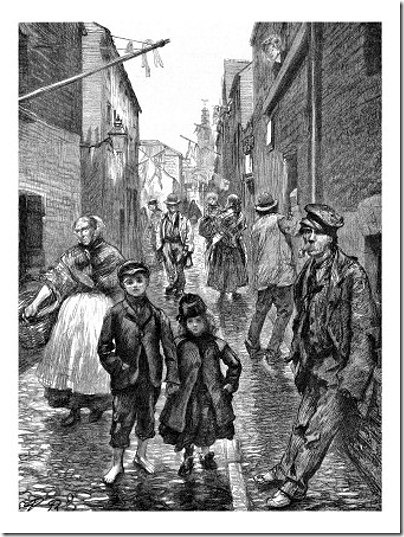

It was about this time William and Caroline Whitfield left Sydney, eventually settling in Picton. That remnant housing in Surry Hills from the 1840s at McElhone Place shown in the last post looked like this earlier in the 20th century – pre-trendy!

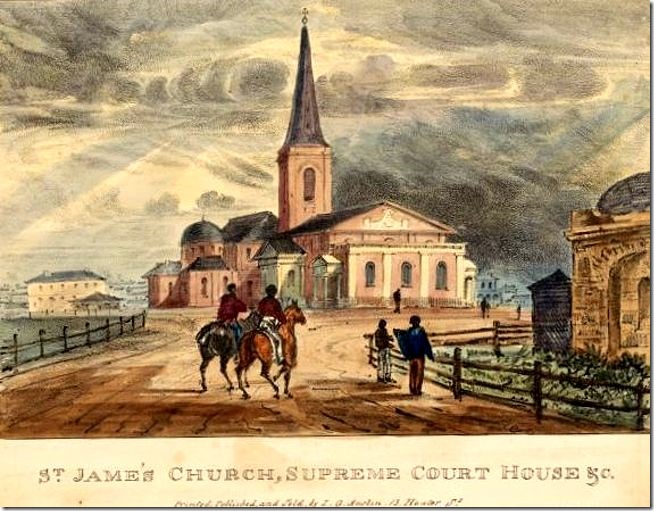

The Harbour was of course already splendid, as this 1845 painting by Jacob Janssen in the Art Gallery of South Australia shows.

That is on the My Place site – an excellent resource for background decade by decade, designed originally to support the excellent ABC children’s television series My Place based on the book by Nadia Wheatley and Donna Rawlins.

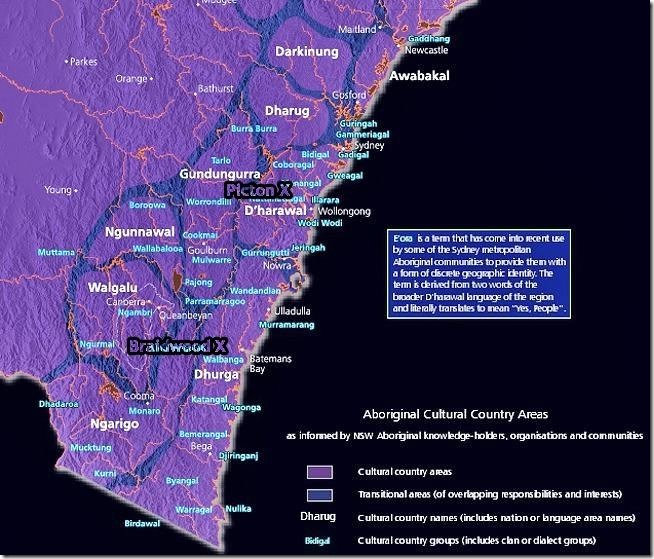

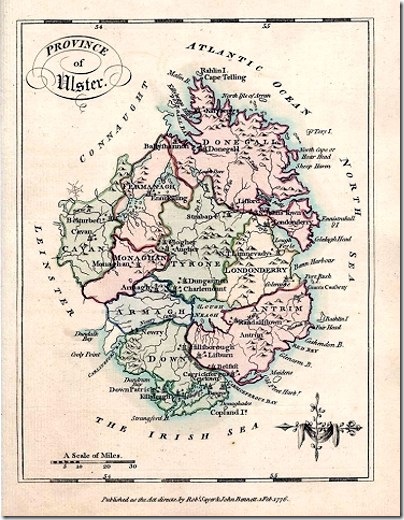

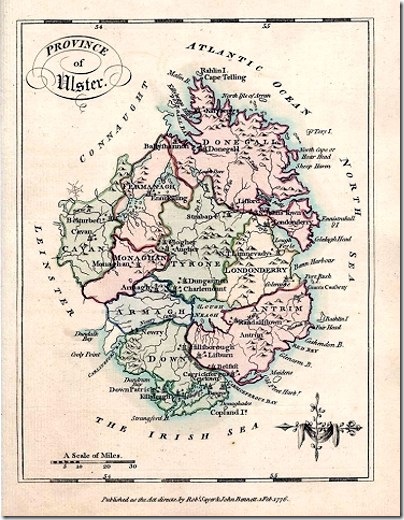

I wonder if the Whitfields of the 1840s kept any kind of contact with their old country, Ulster, which they had left in 1821 (Jacob) and 1825 (William). I also wonder what they would have sounded like, those old Ulstermen….

There’s County Cavan on the left. Not such a good place to have been in 1845, it would appear. See The Great Famine in Cavan.

The Great Irish Famine was, to quote a cliché, a disaster waiting to happen. Between 1750 and 1850 Ireland’s population grew beyond a level at which it could sustain itself. Much of this demographic growth was based on the availability of one food item and when this was withdrawn not just once, but on successive occasions, it resulted in widespread destitution. This was worsened by the structural and ideological failure of those in authority to provide for their sustenance and to prevent the resultant spread of disease.

The population of Ireland on the eve of the Famine stood in excess of 8 millions. The population of Co. Cavan alone was just short of 250,000 – nearly five times its present population. The reasons for this demographic ballooning, which had occurred in the space of little over a century, can be traced to the availability of the potato which provided food security for peasant farmers with little land of indifferent quality. Not surprisingly the potato was adopted with alacrity throughout Ireland, unlike the hostile reception it initially received elsewhere in Europe.

In Cavan and throughout the northern half of Ireland the advent of flax cultivation and domestic linen production had augmented a further security. Areas supplying linen markets like Cootehill became semi-industrialised, as cottages and cabins were modified to deal with the various processes involved in the process of turning flax fibres into cloth. This was sometimes accompanied by the neglect of farm-based food production. When, after 1825 the cottage linen industry collapsed in the face of mechanised production in factories near Belfast, many areas of Ireland, including Co. Cavan, experienced widespread destitution. Ireland lacked industries which could have absorbed surplus agricultural populations, as was the case in the north of England. However there was a growth in urban populations as towns, including Cavan and Cootehill (amongst others) attracted settlers from their rural hinterlands in search of greater though non-existent prosperity of the towns who were confined to unhealthy yet extensive shanty-towns on their peripheries.

The mid 1840s were years of increased tension in Cavan. Acts of physical violence became common. In May 1845 James Gallagher, the under-agent on the Enerys’ estates at Ballyconnell was badly assaulted and died later the same day with forgiveness on his lips for his assailants. Three months later the unpopular George Bell Booth of Crossdoney was assassinated. December 1847 saw the death of the well-known controversialist Father Thomas Maguire. His passing was widely attributed to poisoning, though as the late Fr Dan Gallogly pointed out, this might have been administered by members of his own erstwhile flock who were dissatisfied with his denunciations of physical force methods…

The Famine in Cavan, in common with the rest of Ireland, had its winners and losers. Alas the latter numerically surpassed the former. Those who were already poor and badly-fed were most vulnerable to the food disruption and attendant diseases, and those who came into contact with them, like doctors, were also prone to fall victim to the lethal cocktail of viruses that escaped from the Famine’s Pandora’s box. Others whose positions in society allowed them to eschew contact with the teeming masses, who could afford better food, enjoy more favourable hygiene and heating were insulated from its effects. It is true that while Ireland was in the grip of famine there was no shortage of food in the country. Profits were also made by merchants who exported agricultural items…

The potato famine also affected Scotland.

The eviction of Highlanders from their homes reached a peak in the 1840s and early 1850s. The decision by landlords to take this course of action was based on the fact that the Highland economy had collapsed, while at the same time the population was still rising.

As income from kelp production and black cattle dried up, the landlords saw sheep as a more profitable alternative. The introduction of sheep meant the removal of people. The crofting population was already relying on a potato diet and when the crop failed in the late 1830s and again in the late 1840s, emigration seemed the only alternative to mass starvation.

The policy of the landlord was to clear the poorest Highlanders from the land and maintain those crofters who were capable of paying rent. The Dukes of Argyll and Sutherland and other large landowners financed emigration schemes. Offers of funding were linked to eviction, which left little choice to the crofter. However, the Emigration Act of 1851 made emigration more freely available to the poorest.

The Highlands and Islands Emigration Society was set up to oversee the process of resettlement. Under the scheme a landlord could secure a passage to Australia for a nominee at the cost of £1. Between 1846 and 1857, around 16,533 people of the poorest types, mainly young men, were assisted to emigrate. The greatest loss occurred in the islands, particularly Skye, Mull, the Long Island and the mainland parishes of the Inner Sound….

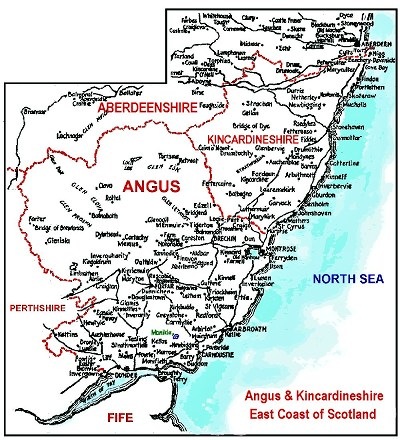

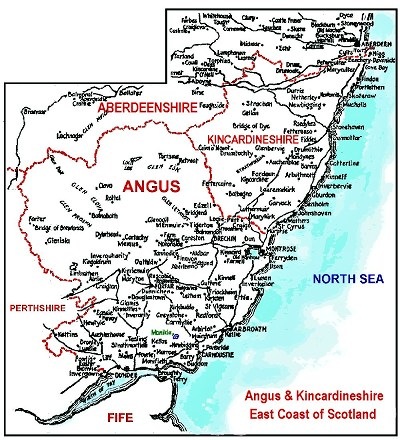

My maternal ancestors, the Christisons, were still in this part of their old country in 1845.

As I previously posted: On my mother’s side of my family – the Christisons – I note my great-great-great-grandfather David was a teenager in 1815, having been born in 1799 in Fettercairn, Kincardine. Seems the poor old sod died in the poorhouse July 21, 1860 of chronic bronchitis. His wife had also died July 2, 1859 in Poorhouse, Luthermuir, Marykirk, Kincardine. That I’d never known before. Note Poorhouses in Scotland “provided medical and nursing care of the elderly and the sick, at a time when there were few hospitals and private medical treatment was beyond the means of the poor.”

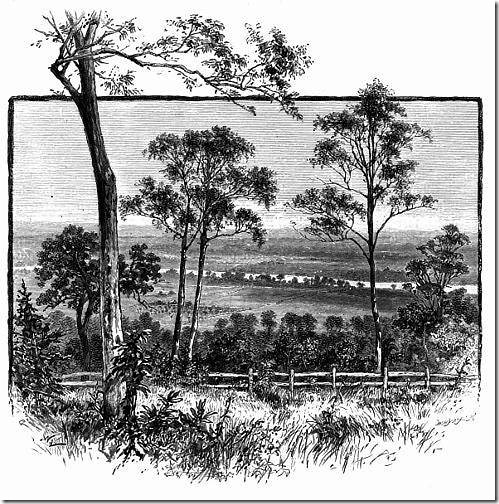

And that brings us back to our local area, to Shellharbour where one branch of the Whitfield family would settle in the late 19th century and in due course marry into the Christison family in 1935.

Caroline Chisholm Park

In 1843 Mrs. Chisholm took up 4 acres at Shellharbour for the settlement of immigrants. In December, 1843 Mrs. Chisholm left Sydney with thirty families totalling 240 people to settle at Shellharbour.

One hundred years later Sir Joseph Carruthers said “Work such as this great and noble woman did ought never be forgotten, least of all in places like Shell Harbour where she did so much for settlement.”

See also:

Caroline Chisholm ‘The Emigrants Friend’ was renowned for assisting immigrant women and families to settle in Australia.

On the 6th December 1843, Caroline brought 23 families of some 240 persons to the harbour at Shellharbour where Captain Robert Towns (son-in-law of D’Arcy Wentworth) as part of Dr Lang’s immigration scheme offered some 4000 acres of land on the Peterborough Estate for families to settle on clearing leases. This allowed families to live rent-free for 6 to 7 years on the land on the condition they clear the land of trees for future farming.

Caroline Chisholm’s diary relates, that when the families boarded the ‘Wollongong’ steamer for the voyage to Shellharbour on 6 December 1843, all stayed on deck until the ship cleared the darkening Heads, then settled down to sleep, while the sea sick lined the rails. The party awoke to a distant view of the beautiful south coast. Some of the children were sea-sick by the time they landed at Shellharbour, the spot most convenient to the proposed settlement’. ‘Fifty-one Pieces of Wedding Cake’-A Biography of Caroline Chisholm – Mary Hoban.

One such family, Matthew Dorrough his wife Martha and their children came with Caroline Chisholm and farmed the area known today as Shell Cove. The family spent their first night under the stars, with the children huddled up under the roots of a large fig tree at the edge of the beach. Next morning they were picked up by bullock dray and transported to the site of their proposed farm. Matthew’s house was adjacent to the beach and he was delegated the job of retaining and issuing the stores to the other settlers on the Estate. He was an experienced farmer and their crops were good, and with the help of his eldest children and Martha, the family prospered.

By 1857, many of the Immigrants had secured or leased homes and properties. The settlers turned mainly to dairy farming. By 1861 the population had grown to 1,415 and land began to open up throughout the whole of the new Municipality of Shellharbour.

Hoban, MC ‘Fifty One Pieces of Wedding Cake: A Biography of Caroline Chisholm, Lowden, 1973.

And this article (PDF) by Neroli Pinkerton:

In 1840, NSW was passing into a depression. Sydney was experiencing high rates of unemployment. Rural labour was needed but the government had no plans for dispersing the throngs of assisted immigrants who remained in Sydney without employment. Caroline Chisholm sent circulars to leading country men seeking

information and enlisting help. In November 1843 she spoke to the Select Committee on Distressed Labourers, telling them that most immigrants emigrate to “live and have land” and she outlined a scheme for settling families on the land with long leases. The government, however. was slow to take up the challenge and unwilling to invest in her schemes. Undaunted, she began the arrangements to settle 23 families on land provided by Robert Towns at Shellharbour …

Incidentally those conditions in Sydney may help to explain why William and Caroline Whitfield left Sydney when they did.